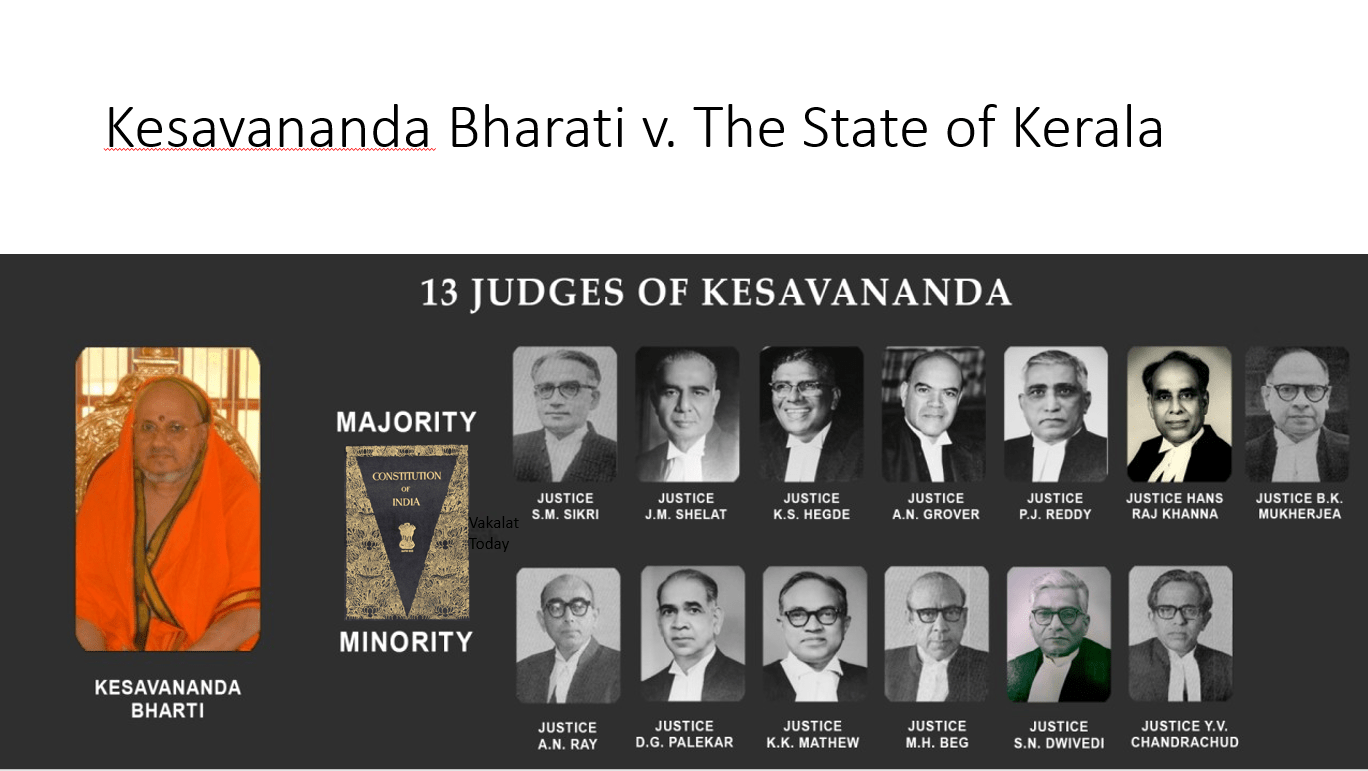

Kesavananda Bharati vs. State of Kerala is a landmark case in the Indian judicial history and also extremely important for students from a constitutional law perspective. This case was heard by a 13-judge bench in the Supreme Court of India, in 1973. The central issue revolved around the scope of the power of the Parliament to amend the Indian Constitution.

The brief summary of the case is as follows:

Background: In 1971, the Kerala government introduced land reform laws that aimed at redistributing land from large landowners to the landless. The petitioner, Kesavananda Bharati, who was the head of a religious institution, challenged these laws on the grounds that they violated the right to property, which used to be a fundamental right at that time.

Key Constitutional Question: The case raised a crucial constitutional question regarding the extent of Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution, specifically Article 368[1]. The petitioner argued that Parliament’s power to amend was not unlimited and that there were implied limitations, especially on amending the basic structure of the Constitution.

The Doctrine of Basic Structure: In a historic decision, the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice Sikri, held that while Parliament had the power to amend the Constitution under Article 368, it did not have the power to destroy or alter its basic structure. The court, however, did not explicitly define what constituted the “basic structure” but identified certain features such as the supremacy of the Constitution, the republican and democratic form of government, federalism, and secularism.

Impact: The Kesavananda Bharati case established the basic structure doctrine, which essentially means that while Parliament has the power to amend the Constitution, it cannot amend its core principles. This doctrine has been crucial in subsequent cases, providing a basis for the judiciary to review and strike down constitutional amendments that infringe upon the basic structure of the Constitution.

The case is considered a landmark in Indian constitutional law as it set the precedent for the limitations on the amending power of the Parliament and reinforced the idea that the judiciary can strike down any amendment passed by Parliament that is in conflict with the basic structure of the Constitution.

[1] The power to amend the Indian Constitution